|

I. The Middle East

At the outset, let me define how the term “Middle East” may be understood. A narrower definition of "Middle East" includes just Egypt, Syria, Israel, Lebanon, Jordan, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, Yemen, Oman, United Arab Emirates, Kuwait, Bahrain and Qatar. A wider definition en-compasses Turkey, Iran, Somalia and Djibouti. Given the much-frequented shipping route between the Black Sea and the Mediterranean (in Turkey), the Suez Canal which connects the Mediterranean and the Red Sea (in Egypt), the Bab-el-Mandeb Strait (between Djibouti and Yemen), and the gateway to the Persian Gulf (between Oman and Iran), the whole area assumes great importance for global trade. Fleets of tankers frequently ply these straits, transporting oil and gas from the Arabian peninsula and Iran to Europe and all of Asia. Commercial ships carry goods between Europe, India, China, Japan, Australia, Indochina, Indonesia and Australia. Port Sultan Qaboos in Muscat and, in particular, the ports of Salala und Duqm on the coast of Oman are designed to become major centres of trade between Europe and Asia. For hundreds of years, the Ottoman and British empires exerted their influence over the entire area with France as their rival; this was followed for the most part by strong US influence. As long as the East-West-conflict dominated international relations, the Soviet Union served – rather effectively – as a counterweight to US influence. Today, Russia is attempting the same role again. The traditional rivalry between Iran and Saudi Arabia has triggered many a conflict in the neighbouring countries and has to be carefully observed, not least given the destruction being wrought in Iraq and Syria. Today, Saudi Arabia and some of the Arab Emirates bomb Yemen back to the stone age. II. European engagement in the area European is primarily interested in establishing and protecting unhindered maritime trade with Asia and East Africa; accordingly, European governments accord prime importance to good relations with both democratic and authoritarian states in the region. Likewise, trouble-free relations with the oil and gas-producing countries of the Middle East are considered to be in the best interest of Europe. This means

Europeans also hope that a higher standard of living in the Arab world and Iran will

groups. III. Indian engagement in the Middle East As long as there is a sizable increase in India’s population, there will be a need for large-scale imports of goods, raw material and energy for India’s industry. India’s rising export industry also needs new markets. Hence, India has a growing interest in the trouble-free passage of goods through the straits of the Middle East. Indian immigrants live in nearly all the Arab countries and Iran. In some of them – for instance Bahrain – Indians even constitute a substantial proportion of the population. India's need for oil and gas resources calls for close relations with all the Middle East countries, irrespective of whether they are more democratic or authoritarian in their political structure. Presently, nearly two-thirds of India's total oil imports come from the Middle East. Given India’s growing Muslim population, every Indian government is concerned with maintaining good relations with the Islamic countries and their ruling elites. By the end of the present century, India's Muslim population is expected to reach about 20% of the country’s total projected population. After Indonesia, this constitutes - equal with Pakistan - the largest number of Muslims in any other single country in the world. The antagonism shown by India’s Hindu radical groups towards Islam resonates negatively with the Middle Eastern countries. That apart, the unresolved conflict over Kashmir serves as an obstacle to India's efforts for good relations with the Arab countries. India has to also reckon with hostile actions on the part of Pakistan to undermine her efforts to strengthen relations with most of the Middle East. IV. European-Indian Potential for Cooperation in the Middle East Europe and India should exploit the potential for cooperation in the Middle East and utilise the opportunities provided by some Middle East countries. 1. Capacity for enhanced trade between Europe and India in Oman’s ports As already mentioned, Oman’s three great ports are designed to become major trade centres. The port of Khasab in Musandam on the Strait of Hormuz is mainly used by fleets of smaller vessels to transport goods between Iran and Saudi Arabia (Arab Emirates) via Oman. Sultan Qaboos bin Said Al Said considers Oman a trading power at the southern tip of the Arabian peninsula. At present, Oman’s harbours serve as the most important ports of call in the Indian Ocean, and for trade between Asia and Europe through the Suez Canal, which was expanded in 2015 for ships with a width of 22 meters and a length of 50 meters. Recently constructed large storehouses provide the infrastructure for transshipment en route to European or Indian destinations, offering intermediate storage facilities for merchandise, oil and gas. It is for this reason that Sultan Qaboosbin Said Al Said pursues a strictly neutral policy. Indian and European shipping companies have been invited to make more intensive use of available capacities. The Sultan has also invited Indian and European construction companies to improve Oman's infrastructure and develop the country’s tourism. 2. Potential for a combined role for India and Europe for resolving the conflict between the Arab countries and Iran Unfortunately, India's present government tilts towards the USA, which bombs the IS and provides financial support to some of the opposition forces. The US especially backs Saudi Arabia in its efforts to topple the Assad regime. The European Union is for unconditional war against IS but not for unconditional support for segments of the opposition forces fighting the Assad regime, for it has to keep in mind that eliminating the Assad regime once and for all may unleash a bitter conflict among the various opposition groups and prolong the devastation in Syria. Who is the lesser evil: the Assad regime or a victorious opposition group which eventually reveals itself to be just as radical as the IS? Combining forces with Russia would mean backing Assad, keeping US influence at bay and opening up the possibility of Assad being replaced in the long run by another president. If India joins forces with the European Union to influence the EU’s trading partners in the Middle East, their combined pressure on Saudi Arabia and Iran could help put an end to the devastation of Syria and Iraq. Both European and Indian governments should remember that it was the Bush administration which, together with Tony Blair's Great Britain, mindlessly unleashed turmoil on the Middle East, when their combined army ousted Iraq’s dictator, Saddam Hussein. Every US government can live with prolonged turmoil in the Middle East. But the fact that the Middle East is so close to the doors of both Europe and India almost inevitably points to the potential for long-term European-Indian cooperation. <img src="http://vg03.met.vgwort.de/na/71cefa716f1c460eae25649917be8996" width="1" height="1" alt="'' />

0 Kommentare

Labour in the twenty-first century

G. Sampath, The Hindu online, February 20, 2016 As the NDA government leans towards industrialists by scripting reforms that would legalise and expand contract labour, the big question is: do India’s trade unions have it in them to resist this imminent legislative blitz? On February 24, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS)-affiliated central trade union Bharatiya Mazdoor Sangh (BMS) will hold a nationwide protest against the National Democratic Alliance government’s labour law reforms. On March 10, all the 11 central trade union organisations (CTUOs), including the BMS, will observe a national protest day. And in end-March, they are planning a mass convention on labour policies to mobilise workers. All this comes in the wake of a 15-point pre-Budget memorandum of demands that the CTUOs had submitted to the Union Finance Minister in January. India’s ‘labour problem’ Ask any top executive from India Inc. and he would tell you that India has a labour problem. And the International Labour Organisation (ILO) would agree. So here’s a quick but unconventional overview of India’s ‘labour problem’. There are eight core ILO Conventions against forced labour. India refuses to ratify four of those: C87 (Freedom of Association and Protection of the Right to Organise Convention); C98 (the Right to Organise and Collective Bargaining Convention); C138 (Minimum Age Convention), and C182 (Worst Forms of Child Labour Convention). India also refuses to ratify another major convention, C131, or the Minimum Wage Fixing Convention. These refusals in themselves present a succinct picture of the status of, as well as the state’s attitude to, labour welfare in India. The Annual Global Rights Index, published by the International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC), rates 141 countries on 97 indicators derived from ILO standards. The rating is on a scale of 1 to 5-plus, based on the degree of respect accorded to workers’ rights. In 2015, India had a rating of 5, the second-worst category. It denotes “no guarantee of rights”. Despite being a constitutional democracy, on the matter of worker rights, India is in the same club as Saudi Arabia, UAE and Qatar, all dictatorships. So yes, India certainly has a labour problem. And a reform of the present labour regime is a must. But what form should this reform take? In 2014, the industry body Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce and Industry (FICCI) and All India Organisation of Employers (AIOE) put out a paper titled “Suggested Labour Policy Reforms”. The paper pointed out that “India’s obsession with an archaic labour policy… is keeping investors away, hindering employment growth and making Indian enterprises uncompetitive”. The paper goes on argue that it is the multiplicity (44 Central and 100-odd at the State-level) of labour laws that is pushing workers to the informal sector, as companies seek “to circumvent the rigorous labour policies”. According to the ILO, “labour market flexibility is as high as 93 per cent in India”. This means that 93 per cent of India’s workforce anyway do not enjoy the protection of India’s 144 labour laws. But industry’s solution to the labour problem is a dilution of these laws so that the mass of informal workers can be employed formally, but without legal protections. Contrary to the ILO-mandated norm of tripartite consultations between employers, the state, and the unions in formulation of labour legislations, the NDA government has been faithfully following the FICCI-AIOE script, brushing aside CTUO demands. Do India’s trade unions have it in them to lead the fight in the face of this legislative blitz? The CTUOs offered a preliminary answer when they came together to pull off a massive general strike on September 2, 2015, which is estimated to have cost the national economy some Rs. 25,000 crore. Only the RSS-affiliated BMS pulled out at the last minute, so as not to embarrass the ruling NDA. Many commentators, however, have dismissed this show of strength as mere tokenism. They point to the increasing irrelevance of trade unions in general, and the CTUOs in particular. First, the argument goes, in a globalised Indian economy, the centre of gravity has shifted from manufacturing to services. Second, even in manufacturing, the advent of global supply chains has meant a mass informalisation of employment as multinational enterprises break up the production process and sub-contract to suppliers in different parts of the world. To cite just one example, as reported by the NGO, the India Committee of the Netherlands, 80 per cent of the garment workers in Bengaluru toil in sweatshop conditions. They Make-in-India for reputed global brands such as Gap, H&M, Tommy Hilfiger and Zara — without ever being employees of Gap, H&M, Tommy Hilfiger or Zara. This kind of employment will become the legal norm for India’s workers when the proposed amendments become law. Such hyper-exploitative industrial zones have been around for a while — from Sriperumbudur in Chennai to Bengaluru to Manesar in the National Capital Region. But India’s CTUOs have so far proved incapable of impeding this onslaught. The fatal flaws The CTUOs’ traditional weaknesses could prove to be fatal flaws in the confrontation between labour and capital in the current economic scenario. The first problem is their political party affiliation. Of the Big Five unions, with a combined claimed membership of over 79 million, the BMS (17.1 million members) owes allegiance to the ruling NDA; Indian National Trade Union Congress (INTUC), with a membership of 33.3 million, is affiliated to the Congress; Centre of Indian Trade Unions (CITU), 5.7 million) is an extension of the Communist Party of India (Marxist); AITUC (All India Trade Union Congress), 14.2 million is a wing of the Communist Party of India; and Hind Mazdoor Sabha (HMS), 9.1 million used to be affiliated to the socialist parties but projects itself as an independent union today. Party affiliations entail three things: one, a restriction of the CTUO’s ability to expand, as it will put off those who do not like its parent party; two, party interests often trump union/labour interests; and three, disunity between the differently-affiliated unions. For instance, the Congress-affiliated INTUC could not get the United Progressive Alliance to curb the rampant violation of labour laws during its 10 long years in power. Similarly, it is evident that the BMS has had no say in the drafting of the NDA’s labour law amendments. While their political masters — the BJP and the Congress — are on the same page so far as labour reforms are concerned, the CTUOs have struggled to forge a united front. Their second big weakness, according to Chennai-based activist V. Baskar, is the leadership, which he believes is marked by the “bureaucratic mentality” of a labour aristocracy. “Is it really workers who are heading the CTUOs?” he asks. “They may have been workers once but today they function more like bureaucrats. They prefer policy analysis to on-ground organising. They have failed to extend their reach to the growing mass of informal workers.” The third weakness has to do with the changing labour landscape. With the majority of the workforce outside the purview of unions, their power to intervene or disrupt has also shrunk proportionately. The pushback on the anvil But the central trade union leaders counter these criticisms. “It is true that we are more focussed on policy issues,” says Tapan Sen, general secretary of CITU. “But that is because it’s an important battle right now. At the same time, we are also involved in struggles on the ground.” INTUC president G. Sanjeeva Reddy points out, “Right now industry is aiming for two things: to legalise and expand contract labour; and to develop in-house unions which will dance to the tunes of the management and stay away from CTUOs.” One sector where the CTUOs do admit to some difficulty is the burgeoning IT services sector, which is marked by little union presence despite demanding work conditions. Says AITUC general secretary and CPI politician Gurudas Dasgupta, “Yes, we haven’t made much headway in the IT sector. Here our biggest challenge has been the instant termination of workers involved in unionising activity. This has created tremendous fear in the minds of the workers.” Adds Mr. Sen: “The state has become such a shameless collaborator that the moment union papers reach the labour department, a call goes to the employer. They obtain the names of the workers who had applied, and terminate all of them.” Harbhajan Singh Sidhu, general secretary of HMS, rejects the charge of disunity among the CTUOs. “All the unions are unanimous on two points: regularisation of contract workers engaged in perennial work; and equal pay for contract workers performing the same job as permanent workers.” Even the BMS has been collaborating with CTUOs of ideologically opposite persuasions. Says B.N. Rai, president, BMS: “We are with the other unions in our opposition to three things: FDI, disinvestment and labour reforms. As for labour reforms, the government can reform all it wants provided three entitlements are not compromised: sufficient wages, job security, and worker security.” Mr. Dasgupta points out that much of the credit for uniting the CTUOs ironically goes to the NDA administration: “The current government’s virulent attempt to crush the trade unions has actually helped build unprecedented unity among the different unions.” Of course, the series of actions planned in March will be a test not only of the CTUO’s unity but also their strength. Mr. Dasgupta rubbishes claims that India’s CTUOs are a spent force rendered even more irrelevant by the absence of a base outside the organised sectors. “The central trade unions are still very strong in the strategic sectors — oil, coal, banking, defence, insurance.” All the union leaders emphasise that the might of the 11 CTUOs is more than the numerical addition of their individual memberships. “During our general strike last year, it wasn’t just the CTUO-affiliated unions but even independent unions and non-unionised workers who participated. All of them are against labour reforms,” says Mr. Sidhu. Summing up, Mr. Reddy strikes a note of conciliation that sounds more like a warning, “The CTUOs have always been open to discussions with the management and the state. But under the current government, the employers and the state are together trying to squash the trade union movement. If they do not listen to us, rest assured that our country is in for major turmoil due to labour unrest.” ([email protected]) With a shift in the centre of economic gravity from manufacturing to services changing the labour landscape, the majority of the workforce is outside the purview of central trade unions Industry seeks to dilute India’s 144 labour laws so that informal workers can be employed formally, but without legal protections The article was first published in The Hindu, India (February 20, 2016) and has been reproduced with permission. <img src="http://vg03.met.vgwort.de/na/ae23375831ae424c8219e5c7c7a36569" width="1" height="1" alt="" /> 1. Strategische Partnerschaft zwischen den USA und Indien

Kanwal Sibal, ehemaliger Foreign Secretary Indiens, analysiert in seinem Artikel „Crosscurrents in India-U.S. ties“ (The Hindu, 16. Juli 2013) die Zweifel Indiens und der USA an der Substanz ihrer strategischen Partnerschaft. Das frühere indische Misstrauen gegenüber den USA sei zwar in der Zwischenzeit von einem positiven Engagement und größerer Akzeptanz US-amerikanischer Goodwill Bekundungen abgelöst worden, aber grundlegende Differenzen blieben weiterhin bestehen. Die indische Regierung müsse zur Kenntnis nehmen, dass die USA in der Förderung „universeller Werte“ eine selektive Verhaltensweise an den Tag legten: Verschonung befreundeter Staaten und Sanktionen gegen Widersacher der USA. Im Falle des Terrorismus erdulde man die Handlungen befreundeter Mächte, während Gegnern der USA der Regimewechsel angedroht werde. Gegenüber Pakistan, Afghanistan, Iran und Syrien sowie beim Klimawandel, in der Doha-Runde, der Souveränität von Staaten und in weltpolitischen Fragen hätten Indien und die USA unterschiedliche Perspektiven. Strategische Partnerschaft, meint Kanwal Sibal, erfordere keine gleiche Sichtweisen und erst recht nicht die einseitige Anpassung Indiens an US-amerikanische Präferenzen, zumal sich Indien mit fehlender Transparenz US-amerikanischer Politik und unangekündigten Strategiewechseln konfrontiert sehe. An den Beispielen Pakistan, Afghanistan und China illustriert Kanwal Sibal Indiens Kopfschütteln über US-amerikanische Politik. Obwohl Pakistan Osama bin Laden beherbergt habe, unterstütze die US-Regierung Pakistan weiterhin militärisch und ökonomisch. Trotz pakistanischer Begünstigung terroristischer Akte gegen Indien unterlägen die USA immer wieder der Tendenz, Indien und Pakistan auf der gleichen Stufe anzusiedeln. In Afghanistan hätten die USA zuerst Indiens Engagement völlig in Frage gestellt, dann unterstützt und jetzt wiesen sie Indiens Zweifel an der politischen Rehabilitation der Taliban durch die USA zurück. US-amerikanische Beziehungen zu China wechselten von der groß angekündigten Fokussierung auf den pazifischen Raum (mit der unausgesprochenen Forderung nach Eindämmung Chinas) zur schwächeren Strategie des „re-balancing“. 2. Visite des US-amerikanischen Außenministers Kerry in Indien Kanwal Sibal kommt anhand des Kommunikees, das nach dem Besuch Kerrys im Juni 2013 die Ergebnisse der Verhandlungen zusammenfasst, zu dem Schluss, dass der „India-U.S. strategic dialogue … ignores or obfuscates key strategic issues“: „The joint statement omits any mention of China Sea or U.S.‘re-balancing’ towards Asia, though Mr. Kerry affirmed in his press statement that the U.S. leadership considered India a key part of such a re-balancing. There is only a general reference – in the paragraph dealing with the Indian Ocean and the Arctic Council – to maritime security, unimpeded commerce and freedom of navigation! Iran and Syria are absent from the statement.” Hingegen als “arm-twisting” bezeichnet Kanwal Sibal Kerrys Forderung, den Vertrag zwischen Westinghouse und der Nuclear Power Corporation of India zur Beschaffung ziviler Nukleartechnologie durch Indien bereits bis zum September dieses Jahres abzuschließen, obwohl viele Fragen zwischen den beteiligten Seiten völlig ungeklärt seien und um unterschriftsreife Formulierungen noch gerungen werden müsse. Abschließend kommentiert Sibal die indisch-US-amerikanischen Beziehungen mit der folgenden Bemerkung: „… the cogs of the strategic partnership still grate with each other and the machine is not adequately lubricated yet by the diplomatic grease of coherence, clarity, balance of interests and a sense of true partnership.” 3. Ein asiatisches Jahrhundert?Die andersartigen Perspektiven, die Indien und die USA mit der strategischen Partnerschaft verbinden und die unterschiedlichen Schlussfolgerungen beleuchtet Rajiv Bhatia in seinem Artikel „Learning to live in a new Asia“ (The Hindu, 9. Juli 2013). Als erstes benennt er die unterschiedlichen Vorstellungen über die Größe und Reichweite der asiatischen Region. In der strategischen Literatur beginne Asien nicht, wie viele in Indien meinten, am Suezkanal und reiche bis zum Japanischen Meer. Asiatische Regierungen und die globale strategische Gemeinschaft bezeichneten mit dem Terminus „Asia-Pacific“ den geographischen Raum, den die Mitglieder des East-Asia Summits (EAS) ausfüllen. Das sind die zehn ASEAN-Mitglieder (Indonesien, Malaysia, Philippinen, Singapur, Thailand, Burma [Myanmar] ,Brunei, Kambodscha, Laos, Vietnam), zusätzlich sechs „dialogue partner“ (China, Indien, Japan, Südkorea, Australien, Neuseeland) und zwei „Pacific“ powers (USA und Russland). Deren Interaktionen hätten den „Asia-Pacific Roundtable“ auf der „major Track II conference“ in Kuala Lumpur zu Anfang Juni dieses Jahres bestimmt. Im Fokus stand die Einschätzung der Politik des Schwergewichts China und dessen Beziehungen mit den USA. Die ASEAN-Staaten unternahmen den vergeblichen Versuch, in Konsultationen und durch Konsensbildung die Nachbarschaftsprobleme mit China in den Griff zu bekommen. Sie scheiterten an den sich aufbauenden fundamentalen Spannungen zwischen Japan und China, dem Konflikt zwischen Nord- und Südkorea und der robusten Einmischung der USA in diesen Konflikt. Chinas Unsicherheit über die gespannte Situation habe sich in zunehmender Aggressivität entladen. Angesichts der vorherrschenden Diskussion des Verhältnisses zwischen den USA und China sei deutlich geworden, dass Indien als „Tier II power“ einzustufen sei. („It may hurt or pride but a realistic assessment shows that India, along with Japan, is a Tier II power, not exactly in the same upper category as China and the U.S. A frank recognition of the fact should help us to craft and pursue a dependable policy to handle Asia’s complexities.”) Was versteht Rajiv Bhatia darunter?

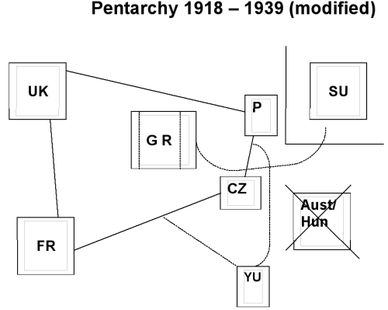

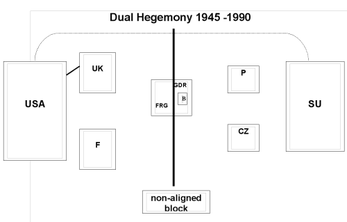

4. Pentarchie (Fünfmächtesystem) und/oder Europäische Union als Vorbild für Asien?Aus dem stetig fortschreitenden Siechtum des von deutschen Fürsten, Königen und Kaisern dominierten „Heiligen Römischen Reichs deutscher Nation“ entstand nach dem Wiener Kongress 1814/15 das europäische Fünfmächtesystem mit den Mitspielern Großbritannien, Frankreich, Russland, Österreich-Ungarn und Preußen. Die drei kontinentalen Flügelmächte Russland, Frankreich und Österreich-Ungarn sorgten für die weitere Schwächung des europäischen Zentrums, das aus vielen Kleinstaaten bestand und sich der Gefahr ausgesetzt sah, vom noch nicht saturierten Preußen aufgesogen zu werden. Das Fünfmächtesystem funktionierte auf folgende Weise: Gerieten beispielsweise Preußen und Österreich-Ungarn in kriegerisch ausgetragene Gebietsstreitigkeiten, sorgten Frankreich und Russland für einen Ausgleich der Kontrahenten und Großbritannien bildete das Zünglein an der Waage. War eine der beiden Zweierkoalitionen zu keinem Kompromiss bereit und reichte der Einfluss des britischen Imperiums entweder nicht aus, um die zum Krieg entschlossenen Mächte rechtzeitig zu beruhigen, oder zeigte die britische Regierung kein Interesse an der Wahrnehmung ihrer Ausgleichsfunktion, weil sie nach dem Aufstieg des Deutschen Reiches den Verlust ihrer Schiedsrichterrolle fürchtete, war ein Krieg unvermeidlich. Die meisten Akteure des Fünfmächtesystems bzw. der Pentarchie des 19. Jahrhunderts zeichneten sich weder durch eine besondere Weitsicht aus, noch beschäftigten sie sich mit dem Fünfmächtesystem als einer endlichen Struktur. Der Weg in den Ersten Weltkrieg blieb ihnen deshalb nicht erspart. Weder erkannten sie frühzeitig die Relevanz der Machtverschiebungen innerhalb des Systems noch waren sie in der Lage, adäquat darauf zu reagieren. Ohne für alle beteiligten Mächte gleichermaßen mit gültigen und anerkannten Werten ausgestattet zu sein, zeigte sich die rein machtorientierte Architektur überfordert und zerbrach schließlich in den Wirren des ersten Weltkrieges (1914 -1918). Die Wiederauflage des Fünfmächtesystems als modifizierte Pentarchie (Großbritannien, Frankreich, Polen, Tschechoslowakei und Deutschland – im Hintergrund mit Jugoslawien als verstärkendes Element der beiden schwächeren östlichen Mitglieder) demonstrierte überdeutlich, wie wenig lernfähig sich die politischen Akteure im Umgang mit den Resultaten des Ersten Weltkrieges zeigten. Ein Sicherheitssystem zu errichten, das ein früheres Mitglied (die revolutionäre Sowjetunion) isoliert, ein zweites Mitglied (Deutschland) in seiner Macht drastisch begrenzt, zum alleinigen Schuldigen für den Ausbruch des Krieges erklärt und beide zu Parias des Systems herabstuft, kann nicht auf Dauer funktionieren und den Frieden zwischen den Völkern erhalten. Der Weg in den Zweiten Weltkrieg war damit zwar nicht vorgezeichnet, aber auch nicht frühzeitig abgewendet. Die Aufteilung Deutschlands in zwei Staaten und Europas in ein amerikanisches und sowjetisches Einflussgebiet schuf für Europa eine völlig neue, von Randmächten beherrschte Sicherheitsarchitektur, die als Ost-West-Konflikt bezeichnet wurde, aber tatsächlich eine duale Hegemonie zwischen den USA und der Sowjetunion darstellte. Nach der verheerenden europäischen Geschichte unternimmt die Europäische Union den Versuch der Zusammenführung bisher selbständiger Zirkulationssphären, deren Glieder weiterhin sehr unterschiedlich ausgeprägt sein können. Der völkerrechtliche Status der EU entspricht weder einem Bundesstaat, in dem die Untergliederungen der Zentralgewalt untergeordnet sind, noch einem Staatenbund mit selbständigen Gliedstaaten. An der EU lässt sich erkennen, welche Probleme gelöst werden müssen, damit eine untereinander abgestimmte Entwicklung zum Vorteil aller gereicht. In ihr werden über Jahrhunderte hinweg unabhängig voneinander gewachsene gesellschaftliche und staatliche Strukturen der einzelnen Nationalstaaten daraufhin analysiert, ob sie in ihrer Fortentwicklung den übrigen Gliedstaaten der EU Schaden zufügen und wenn ja, entweder an die gemeinsame Entwicklung angepasst oder aussortiert werden müssen. Das Zusammenwachsen der EU verlangt nur in wenigen Bereichen eine weitreichende Vereinheitlichung und erlaubt und fördert überall dort separate Ausprägungen, wo sie für den Gesamtzusammenhang nützlich sind und dem Ziel dienen, die Vielheit in der Einheit zu bewahren, zum Nutzen aller zu mehren. Eine ähnliche Entwicklung wie die Schaffung der Europäischen Union ist für Asien unwahrscheinlich. Für die absehbare Zukunft ist beispielsweise eine mit der EU vergleichbare Gemeinschaft zwischen China und Indien nicht vorstellbar. Dies gilt auch für die ASEAN-Staaten, die ihre nationale Souveränität in gleicher Weise wie China und Indien für unantastbar halten. Das Prinzip der Nichteinmischung entsprechend dem Westfälischen Frieden von 1648 gilt uneingeschränkt. Realistischer erscheint eine genaue Prüfung der Mechanismen des Fünfmächtesystems, um aus dem Scheitern der Pentarchie die richtigen Schlussfolgerung ziehen zu können. Endnoteni Siehe dazu: Das ungleiche Verhältnis zwischen China und Indien, in: Reinhard Hildebrandt, Globale und regionale Machtstrukturen – Globale oder duale Hegemonie, Multipolarität oder Ko-Evolution, Frankfurt am Main 2013, S. 157-176. 13 <img src="http://vg03.met.vgwort.de/na/6d89bcb1444a44d4830e8414f702884e" width="1" height="1" alt="" />  On November 25-27, 2009, the conference “Indo-European Dialogue” was held in Brussels and in Paris. The event was organized by the Foundation for European Progressive Studies in collaboration with the French Foundation Jean Jaurès. We publish here Dr. Reinhard Hildebrandt’s discussion paper, titled “Indo-European Dialogue in a Changing World,” for the conference. The following discussion paper is to be situated within the context of the subjects debated at the “Indo-European Dialogue” conference:

I. Introduction

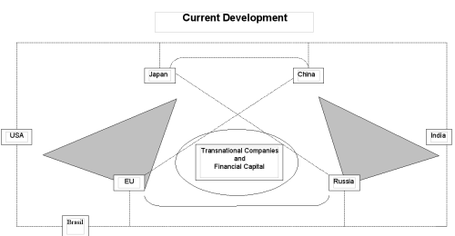

II. A brief review of the past 1.The pentarchy (five-power system): 1815 to 1871 The steady decline of the “Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation”, dominated by German princes, kings and emperors, together with Napoleon’s “daredevil” attempt to build a French empire, led to the emergence of the European five-power system with Great Britain, France, Russia, Austria-Hungary and Prussia as players. Looking at the scenario from the perspective of power politics, it may be said that the three powers of the European flank – Russia, France and Austria-Hungary – contributed to a further weakening of the European center which consisted of many small states. The latter saw themselves faced with the threat of annexation by a still ambitious Prussia. The five-power system operated as follows: If Prussia and Austria-Hungary were for instance locked in a war over territorial disputes, France and Russia maintained a balance between the warring sides while Great Britain was the power that tipped the scales. In weakening the stronger two-power alliance and strengthening the weaker of the two, Great Britain ensured that continental Europe was kept preoccupied with itself, thereby leaving it free to expand its own empire. However this system, guided solely as it was by power politics, was unable to prevent Prussia from expanding its territory and influence over the small German states. 2. A somewhat modified pentarchy following German unification:1872 to 1919 Reacting to the growing endeavors of democratic and nationalist-minded Germans and economic experts to do away with the system of small states and, with that, also shake off regressive princely rule to create a liberal German nation state with a single external customs border, Prussia

The absence of an overarching normative structure straddling the purely power-driven architecture of the pentarchy was now more conspicuous than ever before. Without the same generally accepted values for all the powers involved, the purely power-oriented architecture showed signs of strain and finally collapsed amid the turmoil of the First World War (1914-18). 3. The pentarchy re-configured: 1919 to 1945 The unsuccessful attempt, together with the new allies Poland, Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia, to revive the pentarchy against the isolated revolutionary Soviet Union and the vanquished, severely crippled Germany and finally ended in the Second World War (1939-45) from which the USA and the Soviet Union emerged the new leaders for Europe. The division of Germany into two states, with a divided Berlin as a separate unit, and the division of Europe into an American and a Soviet zone of influence created an entirely new security architecture dominated by peripheral powers – a situation described as indicative of the East-West conflict but in reality reflecting the dual hegemony of the USA and the Soviet Union. 4. The security architecture of the dual hegemony of the USA and the Soviet Union (1945-1990) With the end of American monopoly over the nuclear bomb in 1949 and, more importantly, with the loss of nuclear invincibility in 1959, there emerged for both hegemony-oriented powers a strategic situation in which geo-political stability could be established and maintained exclusively with, and at the same time against, the other in each case. 4.1. The geopolitical ‘with-each-other’ If the geopolitical ‘with-each-other’ were to be considered first, it should be assumed with respect to the implementation of real politics that both hegemonial powers – contrary to their self-perception – were not in a position to exploit all conceivable options for the maximum assertion of their own will. In other words: The assertion of one’s own will curtailed the will of the opposite side to assert itself. The “freedom” of both hegemonial powers henceforth lay in the choice between the options offered by the unfolding of their own power, and the options that could be checked and obstructed, and therefore effectively curtailed, by the opposite side. However, at no point could they assess the exact scope of action open to them. This high measure of uncertainty meant that despite very severe competition, both hegemonial powers shared a common interest in the preservation of the fragile geopolitical stability, particularly in divided Europe and consequently also in their dual hegemony. III. The present re-orientation of the concert of globally engaged powers: (2009/2010) The following developments brought about changes in the global architecture: 1. The Bush administration recklessly frittered away its influence on Russia, which the Clinton administration had come to gain over Russian President Jelzin. 2. After the USA and the EU increasingly began to offer the states of the former Soviet Union membership to the NATO and the EU, while at the same time instrumentalizing the uncertainty created by differences between Russia and the Ukraine over oil and gas supplies in order to advance their own pipeline project circumventing Russia, the Russian President Putin began to increasingly turn to Asia. This shift saw the birth of the “Asian triangle” of which resource-rich Russia is a part along with China and India, and in which the Central Asian Republics are fully engaged. Should the strategic partnerships between China, India and Russia – converging in the “Asian triangle” – result in the emergence of a legal superstructure in the long term, they would, like the EU, become a lasting factor of stability in the global play of powers. 3. An ever-increasing number of Asian economies are turning to China, after the USA – as the largest importer of Asian products until the financial crisis – has now become considerably less important for these markets as a result of the crisis. 4. Some key member countries of the EU, among them Germany in particular, are in turn strengthening their ties with Russia, regarding that country as a useful stepping-stone to Asia. 5. On the Latin American continent – regarded as the USA’s “backyard” during the East-West conflict – only Columbia remains an ally of the US, while Brazil is readying to become a global player. As a consequence of these developments, a new interplay of the global powers appears to be emerging. Economically, the inner Western triangle of USA-Japan-EU still attracts 40 percent of the world trade, but given the activities of the transnational companies and the financial capital involved, even this 40 percent is intensively linked with the emerging Asian triangle of China, India and Russia. Trade within this new triangle is also substantial. The trend towards more globalization remains unbroken although the economic crisis has temporarily curtailed the global flow of financial capital, dented the production volume of transnational companies and caused the rapid decline of the US market. However, we have to take into consideration a shift in global production and trade from the traditional Western triangle to the new Asian one. This development will also have political, military and cultural impacts besides challenging the hegemonic ambitions of the USA. <img src="http://vg03.met.vgwort.de/na/a30d7402d0024513a393bbd1f8135cd2" width="1" height="1" alt="" />

|

RSS-Feed

RSS-Feed